Awareness is key to supporting your child through CPP. Know what your little one is going through so you can care for them with confidence.

Puberty in a nutshell

CPP explained

Puberty, the physical changes that occur over a few years as children develop sexually into teens and then adults, generally includes breast development and menstruation in girls, growth of the testicles and penis in boys, and hair growth plus an overall growth spurt in both. Puberty’s timing can be impacted by genetics, nutrition, and socioeconomic status. It usually starts between ages 8 and 13 for girls and 9 and 14 for boys. If puberty starts earlier, it’s called ‘precocious puberty,’ the most common type of which is central precocious puberty, or CPP.

CPP by the numbers

CPP is rare, affecting about 1 in 5,000 to 10,000 children. Girls are around 10 times more likely to have CPP than boys. African American girls, in particular, are more likely to have CPP than girls of other races, and girls who are significantly overweight are also more prone. Although it’s unclear why, kids adopted from countries outside the U.S. are 10 to 20 times more likely to develop CPP, as well.

Understanding the science

Puberty starts when the brain begins to release pulses or waves of a hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone or GnRH. In response, girls’ ovaries release estrogen, and boys’ testes enlarge and release testosterone. Because bone growth is part of puberty, children with CPP may initially be taller than their friends and classmates, but without CPP treatment, they will stop growing at a younger age and end up shorter as adults. Untreated CPP may also cause psychological and behavioral issues, as developing physically or sexually before peers can be emotionally difficult. Children with CPP who are treated can experience normal development into adulthood. Girls should experience normal periods, and there should be no impact on their ability to become pregnant as adults.

How is CPP diagnosed?

Once your child has been referred to a pediatric endocrinologist, here’s what to expect:

Medical history report and physical examination

Your doctor will capture a robust medical history report (for your child and your whole family), followed by a full physical including an examination of your child’s private areas to check for common signs of CPP. While this last part may seem uncomfortable, it is important for accurate diagnosis.

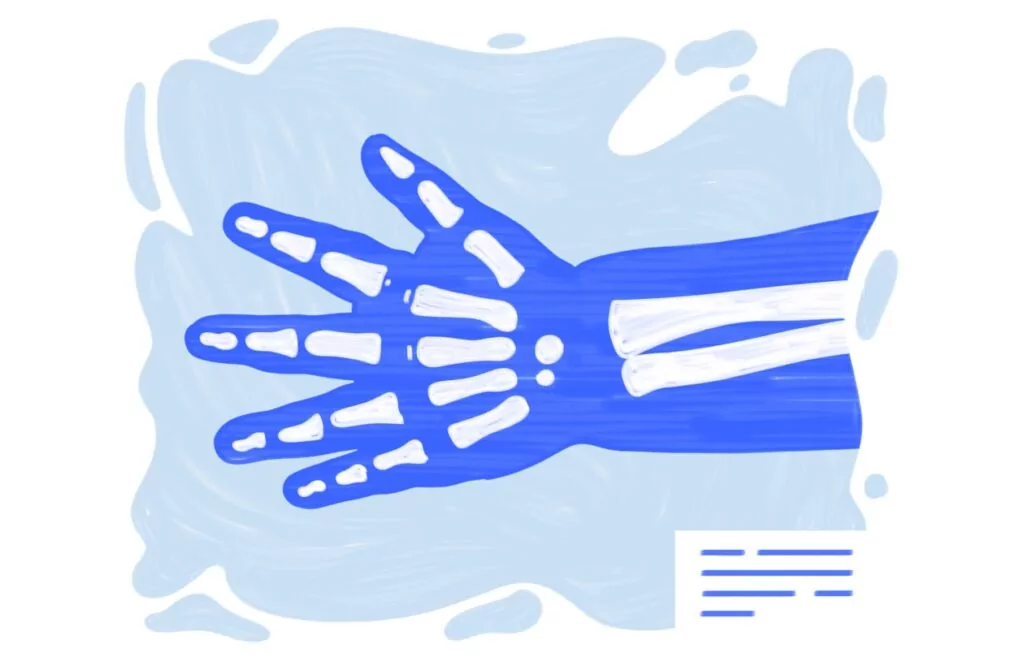

Bone age test and blood test

Your doctor will take an x-ray of your child’s hand to determine bone age. They will then compare these results to standardized bone age charts to determine if your child’s bones are growing too quickly. Blood samples will also be taken to measure various hormones in your child’s bloodstream.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist stimulation test

During this test, GnRH is administered into the body via an IV. After about 40 minutes, the nurse will draw your child’s blood to determine if they have a pubertal response to the hormone.

Pelvic and adrenal ultrasound and MRI or CT can

An ultrasound examines the development of adrenal glands and ovaries or testicles, while an MRI or CT scan determines whether brain abnormalities might be the cause of early puberty.

CPP is treatable

Soon after you start treatment, your kid can get right back to being a kid.

How do you treat CPP?

The good news about CPP is that it’s treatable and it’s not a lifelong condition. Treatments for CPP block the waves of GnRH hormones that trigger puberty until your child reaches an age where it is appropriate for puberty to proceed.

What are my options?

Treatment options for CPP vary in dosing schedule and administration: medicine can be injected just below the skin or directly into the muscle; or treatment can be surgically implanted. You and your pediatric endocrinologist can decide on the best treatment plan for your family.

Treating CPP

It’s important to know that your child’s puberty symptoms may continue to progress for a short time – usually around three weeks – at the start of treatment. After that, though, symptoms should start to improve and your kid can go back to simply being a kid!

TPI.2021.2612.v1 (v1.1)